We fast approach the big day of the big meal,football games, and —for many— some awkward and/or contentious conversation. The different generations and different branches of the family tree pick this day to come together and, well... sometimes they differ. I was at first tempted to mark the day here by once again posting the lyrics to the great Lou and Peter Berryman song "Uncle Dave's Grace" just to poke some fun at the idea. The song tells the sad story of the time Dave is given the honors and with each blessing of the table he cites also the plight of the oppressed and the crimes of society that rendered them. From "grapes in my wine" picked by hunched back laborers to the salad bowl "hacked out of tropical trees" I've always enjoyed the deadpan comedy of the narrator as he notes each of Uncle Dave's many laudable ethical observations, folded so neatly into his prayer, as they slowly drain celebration from the feast —until with the last verse:

We felt so guilty when he was all through

It seemed there was one of two things we could do

Live without food, in the nude, in a cave,

Or next year have someone say grace besides Dave.

But putting that song forward put me in mind of another take on the subject of differences I've been mulling lately. Laughing at the differences that might arise over the dinner table might be one approach, but we all know I like to fancy myself a champion of reasoned debate. I don't mean to dismiss the importance of real differences we might have with one another. I don't mean to tell folks to shy away from issues and considerations that are important to them. But I do want to share the interview I heard a while back with Anthony Appiah on the radio program, On Being.

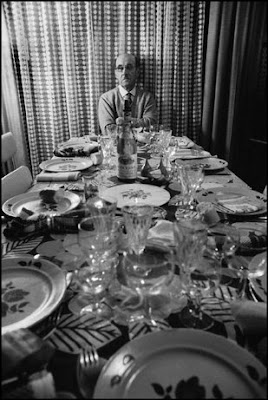

Appiah talks about the idea of "siddling up to difference" as a way, not of avoiding issues and differences, but as a way of approaching them with some other goal in mind, beyond contest. First you find that place where you can recognize the other as essentially human (thus, possibly flawed) —and you recognize the same in yourself and in your own views. Maybe across a table is such a place for that mutual recognition. Towards the end of the Appiah interview you find yourself gathered around a supper table (Julia Childs' table no less):

Mr. Appiah: ... As I say, I wish I spent more of my time around people that disagreed with me more about politics... years ago when I was living in Boston... Julia Childs. I forget when this was, but say this was about 10 or 15 years ago. She was older at that point and her husband had died. She was worried about the state of sort of race discussions in society. So what did she do, being Julia Childs, she summoned a group of people to come and have dinner and talk about it at her house in Cambridge. So there was kind of a mixed-race group around the table. You know, most of us can't do that. You can't just summon people.

Ms. Tippett: But we might be able to do our version of that.

Mr. Appiah: But we could do more of that. Look, one of the great privileges of a free society is that you don't have to spend all your time thinking about the government. So you can easily have a life in which you do almost nothing except vote to participate in the life of the republic. I understand why that is, but if we were to spend more of our time on the life of the republic not directly, you know, by focusing on having more and more political conversations in town halls and some, but by getting together with people in our communities and talking about these things in a way that brought us to a deeper understanding of each other, that would be well worth it, I think.

And the republic would work better because you would be thinking about Joe and Mary and not about conservative Republicans or liberal Democrats and you would know that you knew some awfully nice people who were, for some bizarre reason, not convinced that you are completely correct about every political question.

Amen to that... and pass the gravy.